Annie and Max

Lachowicze is a

small town in Belarus with a population about 10,000. It is 5 km from

Baranovich, 107 km from Pinsk, 150 km east of Poland. It was part of

Poland until 1795, when it came under Russian rule. In 1921 it

reverted to Poland and was ceded again to the U.S.S.R. in 1945.

Throughout the

centuries, the area has had a certain strategic importance.

Situated not far to the north of the great Pripet Marshes, it lies on

the axis between Warsaw and Moscow, through Brest-Litovsk, Minsk and

Smolensk. It was traversed by Napoleon’s armies on

their vain march to Moscow in 1812. Over a century later,

during World War I, it was the scene of heavy fighting between Russia

and Germany.1

In the second

half of the 19th century Lachowicze was a predominantly

Jewish town with 58% of its population of 4000 Jewish. Jews had

settled there by the first quarter of the 17th century. During the

second half of the 18th century, the city’s annual fairs were

important meeting places for Jewish merchants. The stone buildings,

imposing for their time, surrounded the “Market Square”, the

heart of the Jewish life of the town. There was the guesthouse where

itinerant preachers, cantors, travelers, Zionist speakers and

propagandists were found, as well as brides and grooms who used to

meet there with their future spouses. Right in the corner stood the

two-story house of the wealthiest Jew, with a whole row of shops on

the lower level. Another two-story building housed the state liquor

store. Then there was another guesthouse, more modern, where landed

gentry, government inspectors and other state officials lodged.

Further along stood the wooden building with the tailor shop, then

the hospice for the poor, and the house where the Stoliner Chassids

congregated2.

There was the imposing house of an important

merchant of wax, pig's bristle and wood, and further along the shop

of the fish merchant, the furrier, and the supplier of cobblers’

needs.3

Hirsh lived

somewhere along there with his wife, Zlata and their five children,

two sons and three daughters. Chaya Toiba was the youngest of the

three girls. She was a short, slim girl, with a proud bearing. She

looked like someone who knew where she was going and what she wanted

from life. It was said that she was very attractive, indeed

vivacious. There was probably something about her personality,

perhaps an assertive streak of rebelliousness as seen in a photograph

taken some years later that appealed to young men. Suitors, who came

to see her sisters with a view to marriage, wanted to marry her

instead, something unacceptable in that traditional Jewish world; the

older sisters had to be married off first. To get her out of the way

and arrange a marriage for her, Chaya Toiba was sent off to an uncle

in Mogilov4,

some distance away in the Ukraine.

Mogilov was

a much larger Jewish centre, with a number of yeshivas, rabbinical

seminaries. There her uncle found a suitable match for Chaya Toiba, a

rabbinical student, a yeshiva bocher. Marrying a scholar was

considered to be a great honour, the best marriage a girl could wish

for. Chaya Toiba would have been no more than fifteen or sixteen and

her groom not much older. Being a pious boy he had probably never

looked at a girl, had kept his eyes averted in the presence of girls.

He might have been well versed in the arcane arguments of the Talmud,

but very likely didn’t know how to talk to his young wife. They

were just teenagers, but lived very different lives. It was

understood that the wife of a scholar would earn a living, perhaps

run her own little business, support her husband and enable him to

continue to study for the rest of his life. It was an accepted view

among pious Jews that there was only one achievement in life a woman

could hope for – the bringing of happiness into the home by

ministering to her husband and bearing him children5.

This is how things were done. But Chaya Toiba had other ideas. She

insisted that her husband should work and support her. Perhaps some

of the modern notions on the role of women percolated through even to

this remote corner of Eastern Europe. Chaya Toiba had older sisters.

They must have talked about their lives and aspirations. Rachel, one

of the older sisters, was to go to America. There was change and

restlessness in the air. Chaya Toiba wanted to strike out on her own,

live her own life. She sought a life beyond the confines of the

traditional Jewish world. She had enough of her scholar husband and

wanted a divorce. According to Jewish law, it is the husband’s

prerogative to grant his wife a divorce and this Chaya Toiba’s

husband refused to do. Perhaps he thought that he was on to a good

thing, or the shame of parting with a wife whom he had only recently

married was more than he could bear. There might have been also the

important matter of the dowry, which would have gone some way towards

supporting him. So Chaya Toiba threatened that unless he agreed to a

divorce she would go to the Cossacks and tell them that her meek,

quiet, scholarly husband was a revolutionary. But who knows, perhaps

Chaya Toiba didn’t make this up. New radical ideas were sweeping

Russia. Czar Alexander II was assassinated but a few years before,

and his successor was even more autocratic. Violent pogroms followed

the assassination and became a regular feature of Jewish existence.

Jewish young men and women were discussing the life and fate of Jews,

Some believed that Jewish life was doomed under the oppressive regime

of the Czar, that the whole autocratic regime had to be overthrown.

Others had argued that there was no future for Jews in Russia at all,

that Jews had to pack up and move to Palestine, the backward province

of the Ottoman Empire, to the settlements that a British financier

funded. Perhaps Chaya Toiba’s young groom had dangerous ideas

unbecoming to a Jewish religious scholar, or Chaya Toiba herself

wanted a different life for herself and was determined to move on. At

any rate, she had her ways of getting what she wanted.

Leaving her

husband and the scandal of her divorce behind, she took off to

Yekaterinoslav, now Dnipropetrovsk,6

the third largest city of the Ukraine. It was an important centre of

Jewish life, with the history of Jewish settlement going back to the

foundation of the city in1776. We don’t know whether she moved

there with Menachem Mendel Darevsky, or the two ended up there

separately. Nobody seems to

know how or where the two had met.

He might have been the cause of the divorce. Menachem Mendel, though

originally from Mogilev, had family in Yekaterinoslav. A few years

younger than Chaya Toiba, she fell in love with him and wanted to

marry him, but the father of Menachem Mendel thought that his son

could do better than marrying a divorced woman, older than him,

without a substantial dowry.7

Menachem

Mendel was born in Mogilov in 1876, son of Shlomo Darevski. He seems

to have come from a relatively well-to-do traditional Russian Jewish

family. On a photo that survived he is seen sitting in front of

Chaya Toiba, a handsome, sensitive looking young man, looking more

like an earnest schoolboy than a newly married man. Chaya Toiba

stands behind him, erect, confident, clearly the dominant partner. He

was three years her junior.

There were

Darevskys in Lachowicze. The name derived from Darevo, a small hamlet

near Lachowicze, where there were Darevskys who were publicans.

We don’t

know what Menachem Mendel was doing in Yekaterinoslav. Yekaterinoslav

was a rapidly growing city, with new industries founded or managed by

Jewish entrepreneurs. Although Menachem Mendel was hardly more than a

teenager, either business or educational opportunities might have

brought him there. He was described as a tailor in the passenger list

of the ship that brought him to New Zealand, but we don’t know

whether he worked as a tailor in Yekaterinoslav. He might have had

other ambitions and a glowing vision of his future.

Not having

had the family’s approval, Chaya Toiba and Menachem Mendel eloped

and left Russia, possibly sailing from Sebastopol. Life for Jews was

becoming increasingly intolerable. There were pogroms, and frequently

new regulations were introduced, which limited the places where Jews

could live and how they could earn their living. Their educational

opportunities were circumscribed. After the assassination of Czar

Alexander II in 1861, and the Polish revolt of 1863 the oppression of

Jews accelerated. By the 1890s well over 100,000 Jews had left Russia

every year. Most of them headed for America, but some went to South

Africa, to Britain, and to various countries of Western Europe. Chaya

Toiba’s older sister, Rachel might have already gone to America.

Chaya Toiba and Menachem Mendel might have thought of joining her.

However they only made it as far as London where they might have had

some distant relatives. There they found that the foggy climate and

the damp polluted air didn’t agree with Menachem Mendel’s weak

chest. Perhaps life in Whitechapel, the impoverished, crowded Jewish

quarter of London was not what they had in mind when they left

Yekaterinoslav. Someone had told them to move to New Zealand for a

better climate and a better life. A new sanatorium had just been

opened in Otaki, an old Maori settlement 70 km north of Wellington.

Between Yekaterinoslav and Otaki Max Darevsky became Max Deckston

and Chaya Toiba became Annie. They sailed to New Zealand on the

Ionic, a ship that left London on 20 December 1899, and arrived in

Wellington on 5 March 1900. They appear on the ship’s log as Morris

Dickstein, tailor, not yet Max, and Annie Dickstein, occupation none.

Among the many Irish, some Scots and quite a few English, they were

included with the very few described as ‘foreigners’.8

You leave Russia, you leave the world where you are known, and you

can become anyone you choose to be. They went Otaki when they

arrived. Otaki was a centre of market gardening. Resourceful young

couple that Annie and Max were, they set up on a small farmlet,

grew their own produce, had a cow and generally must have sold

some of their produce, and the couple prospered.9

Max’s health improved. Soon they moved to the Hutt Valley, and

leased a farm, known as Captain Mann’s property, in Orr’s Road.10

We don’t know how they got into farming, or how much they knew

about farming. One of Annie’s uncles was a dairyman.11

He had perhaps a few cows and sold milk, cottage cheese and other

dairy products. A cow in Lachowicze was not that different from a cow

in Lower Hutt. Annie must have thought that there is more of a future

in farming than in tailoring. There were too many poor Jewish tailors

in London. By the time the lease on their farm was up in 1904, only a

few years after they had started farming there, they owned 15 dairy

cows, 15 heads of young stock, 1 light draught mare, 1 trap horse, a

dog-cart with harness, and lots of furniture. These were the items

listed to be auctioned at the end of their lease.12

They left the farm. They were well established, but they traveled

light. They must have moved on to another farm, because in February

1906 Max Deckston was convicted of allowing cattle to wander.13

Annie and

Max were clearly difficult and cantankerous people, or perhaps they

just stood up for their rights and would not put up with insults.

Recent arrivals though the Deckstons were, they went in for

litigation. This was not Russia, Jews, like everyone else, had

rights, and Annie and Max relished these rights. In February 1902

they charged Benjamin and Jacob Semeloff, fellow members of the small

Jewish community in Wellington with assault.14

The Semeloffs had been in New Zealand longer than the Deckstons. They

were established businessmen, pawnbrokers, auctioneers, and later

building contractors and property developers. They were not averse to

litigation either. It is possible that having initially fallen out,

the Deckstons later learned from the Semeloffs. They both acquired

property in Newtown. Max and the Semeloff brothers were also involved

with the Wellington Zionists’ Social Club, the precursor of the

Wellington Jewish Social Club.15

A number of

assault charges were laid by Annie and Max against various people. In

August 1905 four men were charged with assaulting Max Deckston, a

dairy farmer, but after hearing evidence, the bench dismissed the

case. In 1910 they charged three brothers with assault. Two of them

were convicted; the charge against the third was dismissed. The

brothers, in turn brought countercharges against Max. Though this was

dismissed, clearly there were two sides to the story.16

In 1906

Annie and Max were naturalised. They were very proud of their British

nationality. To the astonishment of the officer who handled the

matter, Annie insisted on getting her letter of naturalisation in her

own name, even though being married to Max, who was himself

naturalised, she was automatically a naturalised British subject.

Unlike other women of her time she insisted on being treated as a

person in her own right.

In 1908

Annie and Max were on the move again. They leased another farm, this

time in Taita, about three miles, five km from Lower Hutt, adjacent

to the Taita Hotel. There was a problem with the lease; it was

executed by the Pakeha wife of a Maori. Pakehas had no authority to

dispose of Maori land, but ultimately the matter was resolved and

they kept the lease as long as they lived.

Max and

Annie had lived a rather isolated life for some years, in the Hutt

Valley, far from any Jewish community, yet keeping an observant,

kosher Jewish home. They would have traveled to Wellington whenever

they could to participate in Jewish life. In 1908 Max was given the

honour of finishing the writing of the Sefer Torah, the scroll,

presented by J. E. Nathan to the Wellington Jewish community.17

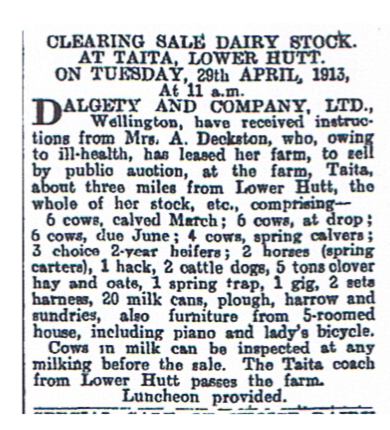

Max and

Annie appeared to have prospered, but in 1913, they decided to sell

up, give up working on the farm themselves because Max’s health was

no longer up to it. They sold their chattel, which included by then,

among other items, 25 cows, three horses, and a five-bedroom house

with a piano.

They kept

the lease of the land, but after that the farm was worked by hired

hands.

Annie and

Max moved to Wellington, bought a place right in the middle of the

city at 32 College Street, and they had some money left to invest. It

is likely that they took their time finding their bearings, talking

to people, and gathering ideas. Perhaps they met up with the Semeloff

brothers, Benjamin and Jacob, and sounded them out on how to make

best use of their capital. The Semeloffs had been in business for

many years as traveling merchants, property owners, developers,

pawnbrokers, moneylenders and auctioneers.

Annie and

Max were sensitive about being seen as foreigners. A letter in the

Evening Post in December 1913, soon after their move to Wellington,

alleged ‘that a good deal was

heard about foreigners being responsible for the waterfront strike

….’ The writer of the

letter said that he himself was working on the wharves and was

thankful for being granted the rights and liberty of a British

subject, that he had some land and property that he got through hard

work, and that were the Red Feds allowed to win the strike nobody’s

property would be safe. Annie, and again, Annie and not Max, called

on the newspaper to explain that ‘her

husband was much concerned, because some people were accusing him of

being the author of that letter. He had been, she stated, in no way

responsible for the letter. He never wrote and never asked anyone to

write it. It was true that her husband was a naturalised Britisher,

and had bought a little property out of his savings, but he had never

worked on the wharves, and had never given expression to the

sentiments contained in the letter.18

In 1917, a

while after leaving their farm, Annie and Max bought a pawnbroker

business at 50 Courtenay Place, opposite the Paramount Theatre.

This, or

similar advertisements appeared in the newspaper weekly if not daily.

They advertised that they were ‘Buyers

of New and Second-hand Clothing, Boots, and Musical Instruments,

etc.’ and ‘had Money to Lend on anything’. There were a number

of Jewish pawnbrokers in town. In June 1920, a thief, who specialized

in stolen overcoats, was caught. He sold one coat to Spolski in

Taranaki Street, another to Brickman in Courtenay Place, yet another

to Mrs. Levy in Manners Street, and one to Mrs. Nausbaum, also in

Manners Street, all well known identities within the Jewish

community.19

Annie and

Max also invested their money in properties. The years after the

First World War was a time of rapid growth of the city. Buying

residential property in College Street, Vivian Street, Courtenay

Place, Newtown and Berhampore, parts of the city that were soon to

change from residential to commercial areas, proved to be good

investment. Most of the properties were in the name of Annie

Deckston, though there were some in Max’s name. They didn’t own

property jointly. But being landlords and owning properties were not

without problems. Annie bought the lease on seven houses situated on

the corner of Vivian and College Street, with a view to demolishing

them and developing the site, but because of the housing shortage

after the First World War, she could not evict the tenants, nor could

she increase the rent.20

Collecting the rent was at times also risky. One of her tenants, a

war veteran, tried to start a taxi business, but the business failed

owing a good deal of money. when he was declared bankrupt Annie

Deckston was his largest creditor.21

Always a

businesswoman, Annie explored other business opportunities as well.

She decided to manufacture Matzot, Passover bread. She agreed to

purchase second-hand biscuit making machinery from a business that

went bankrupt, but found that these did not serve the purpose, she

was not prepared to pay for them, and wanted to renege on the deal.

The seller of the equipment sued, and after numerous adjournments the

Court found in favour of the plaintiff. Annie probably thought that

there was a principle at stake. It was not easy to get money from

her.

Annie and

Max also kept their interest in the farm in Taita, and acquired other

farms, but these also proved troublesome. The ownership of some land

Annie leased from native owners was in dispute. The argument about

who was entitled to share in the rent ended up in court22.

In another instance she tried to eject a tenant for failing to

maintain the property23

Again the matter had to be resolved though litigation. Annie was a

tough landlord and didn’t hesitate to sue to assert her right.

Over the

years Annie and Max accumulated considerable wealth. Once they moved

to Wellington they became involved in the Jewish Social Club. In

1919, Max, by then clearly wealthy and happy to show off his wealth,

offered a portion of his land in Vivian Street for the club on which

to erect a suitable building. This offer was turned down, the cost of

the building was estimated to be approximately £7,000, way beyond

the resources of the Club, but later the Club bought a property 86

Ghuznee Street for £3,000. Max was co-opted, together with his

former adversary Ben Semeloff, by then a builder and property

developer, on to the building fund committee.

By the

1920s Annie and Max had been established, well off, and they decided

to find out what happened to the families they had left behind in

Russia and what was by then, Poland. In January 1923, they auctioned

off all their stock. They were leaving. The following advertisement

appeared in the Evening Post on 18

January 192424

As

the shop is leased from Monday, Every lot will be Sold WITHOUT

RESERVE

They

clearly dealt in a great variety of merchandise.

They had

been in New Zealand, cut off from their home for over twenty years.

Annie could neither read nor write, certainly not in English. Jewish

girls of her generation, growing up in the traditional Eastern

European Jewish world were taught practical skills, such as running a

home and a business. Reading and writing and the study of the holy

books were left to the men. Annie was a shrewd businesswoman, but she

could not write letters home to her family. She knew that she had a

sister in America. To find her she and Max went to Chicago in 1924,

called on the Landsmanschaft (Society for Expatriate Compatriots) who

helped her to track down Rachel, her sister. When Annie turned up on

her doorstep Rachel didn’t recognise her. She was suspicious. She

had not heard from Annie all those years and could not be sure that

she was still alive. Annie managed to convince her that she was

indeed who she said she was by showing her an identifying birthmark.

From her sister, Annie found out that her younger brother and his

wife with their family were alive and living in Bialystock in Poland.

Annie and Max went to visit them and persuaded them to move to New

Zealand. She held out to them the prospect of a better, more

prosperous life. Ultimately more of her nieces and nephews came to

join them, while Max got in touch with his sister’s family in

Russia. Some, who had lived comfortable middle class lives before,

had a hard time after the Bolshevik revolution. A number of these

were also persuaded to move to New Zealand.25

Annie and Max paid for the passages of many of their relatives. They

brought, over a few years, 40 members of their family to Wellington26.

These formed a significant Russian Polish Yiddish speaking sub-group

within the local Jewish community.

Annie and Max

perhaps hoped that having a large extended family around them would

break down their isolation. Somehow things didn’t work out well.

Annie was a strong-willed domineering woman, spiteful, according to

one of her nieces. She knew how to get by in New Zealand. She could

tell her greenhorn newly arrived relatives how to live their lives.

Some of the relatives resented that they were put to work on the

farms or in one of the shops that Annie and Max had interest in, a

fruit shop among them. Perhaps they thought that they had not given

up their more comfortable life style in Poland to do menial work

here. It is possible that some expected more help from their wealthy

benefactors. They deferred to Annie and Max, called them Auntie and

Uncle, they visited them in their spacious large home on the hill in

Hataitai, but could not help but compare that with the austere, small

simple homes that they themselves lived in.

Annie believed in

hard work, frugality, and making money. She didn’t approve of

higher education. When one of the nephews wanted to go to university

and study medicine she refused to help. Marrying off their niece was

something else; in the world they grew up in providing for the bride

was a mitzvah, a meritorious act, a religious obligation. Annie and

Max put on a lavish wedding with 300 guests for one of the newly

arrived nieces. The wedding was as much a celebration of the opulence

of Annie and Max as a celebration of the marriage of a couple

starting a new life together in a new country, but having a

photographer take pictures at the wedding was in Annie’s view, a

frivolous waste of money. The couple resented this petty penny

pinching. Annie was insensitive to the feelings of others.27

Over the years Annie and Max fell out with many of the relatives whom

they had brought out from Russia and Poland. If they had hoped to

surround themselves with a warm loving family they were disappointed.

After their

return from Europe Annie and Max were preoccupied with the farms that

they leased. Even if Annie and Max no longer worked on their farms

they continued to be actively involved with them. They also had their

city properties to manage, with all the problems these entailed.

There were fires; there were tenants who could not pay their rent.

The Deckstons embarked on property development, and called for

tenders for the erection of brick and concrete building in Vivian

Street28.

Such developments were welcomed. The housing conditions had greatly

improved as the result of the commercial development of the city, and

among of the examples cited were Deckston’s warehouses

These

buildings had resulted in the demolition of very large numbers of

small and dilapidated house properties and the erection in their

place of up-to date commercial premises29

Annie also dabbled in other enterprises whenever the opportunity

presented itself. She had a small parcel of shares in a taxi and

trucking company30.

Notably, it was Annie and not Max who owned the properties and

shares. A fire occurred in one of the properties in her name in

Adelaide Road, which also slightly damaged the adjoining building

described in the newspaper as belonging to Mr. Max Deckston, Annie

took the trouble to get the newspaper to correct this, and print that

she owned both properties. Max’s role was to be Annie’s husband,

a well-known identity in the city whose large American car was widely

recognised, partly because of his insistence that the usual traffic

and parking rules didn’t apply to him.

In 1932 Annie and Max returned to

Poland for a visit. There they were shocked by the plight of some

Jewish children in orphanages. Poland was hard hit by the depression

and it impacted on Bialystok, a major centre of textile manufacture,

especially Poverty was evident everywhere. Some families could no

longer support their children and handed them over to orphanages,

others were beset by tragedy and could no longer care for their

children. But unlike orphanages in other parts of the world,

including some in New Zealand, orphanages in Poland were benign,

caring, humane institutions.

On their way home

to New Zealand Annie and Max met an eight-year-old orphan daughter of

a relative in London and adopted her. They now had an adopted

daughter. They also decided to bring some orphans from the Jewish

orphanages in Bialystok to New Zealand and provide a home for them.

Being the practical, can-do people that they were, they applied for

entry permits for these children. They got the president of the

Wellington Jewish Community to lobby on their behalf;31

Annie herself called on officials and thumped their desks until she

got what she wanted. They arranged for the immigration of at first

eight children in 1935 and in 1937 brought out a further twelve, 20

altogether. They tried to bring out a third group a while later, but

by then the NZ Government placed insurmountable obstacles in their

way and these children were left to their fate in Poland.32

Some of these were children of relatives. Each group was accompanies

by a couple related to Annie. Annie and Max bought a large property

in Berhampore, and set up a Jewish orphanage, where all the kosher

dietary laws were observed, and daily prayers were recited. It was a

little island of Jewish observance. Annie and Max were now aunt and

uncle to a large family of children. There were little girls who

sorely missed the homes they came from, unruly teenagers who felt out

of depth and bewildered, some resented that they were rescued while

their brothers and sisters, the rest of what was left of their

families were abandoned. There was a lot of bitterness within this

large, chaotic home. Annie and Max didn’t know how to manage

children, they never had any of their own and being in their sixties

they didn’t have the patience that bringing up children required.

Some of the children remembered Annie with little affection, as a

tough woman. She beat them, locked them up as punishment, and she was

frugal to the point of meanness. Max was kind to the girls, but tough

on the boys. He tried to provide them with a rudimentary Jewish

education. He taught them harshly, demanding attention and

application as probably he himself had been taught. These children

had to learn to survive in two different worlds; in their secular

schools, where they were probably bewildered not only by the

language, but also by the strange customs of New Zealanders, had to

cope with subjects new to them, play sports and games unknown in

Poland, and they were probably bullied, picked on, ridiculed, then

back in the orphanage they had to face the harsh regime imposed on

them by their elderly guardians and the strict uncompromising Jewish

observance of the home. It was a hard life for these children. The

orphanages in Poland they came from were probably enlightened

institutions, influenced by the teachings and example of Janusz

Korczak, Polish-Jewish educator, children's

author, pediatrician

and director of a Warsaw orphanage. But if life was tough for these

children, it was no worse, might have even been better, than life in

other orphanage in New Zealand in those days. Although at the time

Annie and Max could not have realised this, they also saved these

children from the Holocaust by bringing them to New Zealand.

When Annie was

interviewed after the arrival of the first set of eight children she

said “I knew what it was like for them years ago and I know what

it is like for them today. I know what it has been for my people, the

children and the grown-ups. I have had a sorrowful life,” 33.

The interviewer assumed that she was thinking of the hard life of

Jews in Poland, but who knows, perhaps she was also thinking of her

35 years in New Zealand, where she struggled to earn a living and

make enough money to be able to help her family, perhaps she thought

of their isolation in this country where they stood out as being

different, where Max faced assaults repeatedly, though possibly he

invited these assaults, where they were too foreign, too Jewish not

only for the New Zealanders around them, but also for the local,

largely British Jewish community. Eastern Jews, Polish Jews were a

source of embarrassment to the assimilated Jews of the colony.

Annie died in

1938 aged 67, Max died a year later. The orphanage was neglected,

mismanaged by a series of unsatisfactory matrons. It was put in the

care of trustees, who assumed responsibility fir it until all the

orphans grew up and left the home to live independent lives of their

own. Most of them left New Zealand; moved to Melbourne where there

was a large community of people from Bialystok, some became very

successful entrepreneurs, businessmen, the girls married, brought up

families.

When in the end

there were no orphans left to justify keeping the orphanage going,

the property was sold, and the considerable estate of Annie and Max

Deckston, which comprised of numerous properties around Wellington

and some farms in the Hutt Valley, was used to establish a Jewish old

age home, in Naenae, which to this day is called the Deckston Home,

though it is no longer a Jewish home that provides kosher meals and

Jewish pastoral care for its few Jewish residents.

Annie and Max

were not much loved in their lifetime, and they are scarcely

remembered in the annals of the Wellington Jewish community. There is

a street named after them in Taita, Lower Hutt, but few know who the

street was named after. Yet Annie and Max cast a very long shadow and

their legacy continues to this day, many years after their death.

There is still a wing of an old age home named after them, their

substantial legacy is used partly to assist the elderly Jewish

residents of Wellington, partly and very appropriately, to further

Jewish education in this remote part of the world.

On June 27, 1941,

the Nazis occupied Bialystok, the city of the 20 children whom Annie

and Max rescued,. Bialystok was a predominantly Jewish city. At the

time it had 50,000 Jewish inhabitants, 350,000 in the province. On

the day following the German occupation, known as "Red Friday",

the Germans burned down the Jewish quarter, including the synagogue

and at least 2000 Jews who had been driven inside34.

The family of one of the Deckston children was among these. Other

similar events followed in rapid succession: on Thursday, July 3, 300

of the Jewish intelligentsia were rounded up and taken to a field

outside the town and murdered there.The

Germans embarked upon the liquidation of the Jews on February 5-12,

1943, when the first Aktion in the Ghetto took place. In July the

united Jewish underground called upon the Jews to fight. They engaged

in an open battle with the Germans. The Ghetto fighters held out for

another month, and night after night the gunfire reverberated through

Bialystok. A

month later, the Germans announced the completion of the Aktion in

which some 40,000 Jews were deported to Treblinka and Majdanek. 35

Three boys from one of the orphanages hanged themselves as an act of

defiance. Even the German soldiers who witnessed it were moved. It is

believed that one of these boys was the brother of a girl in the

Deckston orphanage.

1

Lachowicze, Belarus

http://www.familytreeexpert.com/fte/countries/belarus/lachowicze/lachowicze.htm

3

Avrom Lev. A

Walk through My Devastated Shtetl,

1952,

http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Lyakhovichi/townhistory-Lev.htm

4Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogilev

5

Kreitman, Esther, Deborah, Virago, London, 1983, P.

6

Jewish Community of Dnepropetrovsk online

http://djc.com.ua/index.aspx?page=content&mnu=1&type=History&lang=en

8

NZ National Archives ss 1/471 No.12

10

Evening Post 19 March 1904

11

Street and Business Guides

to Lyakhovichi and its surrounding communities, Using Lyakhovichi

City Directories by

Deborah Glassman, 2007,

http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Lyakhovichi/BusinessDirectoriesofLyakhovichi.htm

12

Evening Post 19 March 1904

13

Evening Post 14 February 1906

14

Evening Post 26 February 1902 P.6

15

A standard for the people: the 150th anniversary of the Wellington

Hebrew Congregation, 1843-1993, edited by Stephen Levine,

Christchurch, N.Z.: Hazard Press Publishers, c1994, p.168

also Evening Post, Volume LXVII,

Issue 26, 1 February 1904, Page 5

16

Evening Post 23 September 1910 P.2

17

A standard for the people, p.77.

18

Evening

Post, Volume LXXXVI, Issue 134, 3 December 1913, Page 8

19

Evening

Post, Volume XCIX, Issue 147, 22 June 1920, Page 4

20

Evening

Post, Volume CI, Issue 40, 16 February 1921, Page 2

21

Evening

Post, Volume CII, Issue 16, 21 July 1921, Page 7

22

Evening Post, Volume LXXXVII,

Issue 123, 26 May 1914, Page 7

23

Evening

Post, Volume XCVIII, Issue 50, 28 August 1919, Page 8

24

Evening

Post, Volume CVII, Issue 15, 18 January 1924, Page 12

25

A standard for the people, p. 392ff

26

N.Z. Radio Record, Vol. XII, No. 50, Friday, May 26, 1939, P.1

27

Solly Faine, The Family Narrative, July 2007, unpublished

28

Evening

Post, Volume CVI, Issue 13, 18 July 1928, Page 20

29

Evening

Post, Volume CXXIV, Issue 114, 10 November 1937, Page 13

30

Evening

Post, Volume CVI, Issue 75, 9 October 1928, Page 12

31

A standard for the people, p.141

32

N.Z. Radio Record, Vol. XII, No. 50, Friday, May 26, 1939, P.2

33

Jewish Review, June 1935, p.15

34

We Remember Bialystok! http://www.zchor.org/bialystok/bialystok.htm

35

ibid